Dung Trans’ business is booming: “Last year, we added a second floor to our factory. And now I’m looking at a new site four times larger than the current one.” For his company, Spartronics, an electronics maker, the ongoing trade dispute between China and the United States has been a boon. And he is not alone.

The United States and China have been locked in a trade dispute for more than two years. Between July 2018 and September 2019, the US slapped tariffs of up to 25% on almost all imports from China.

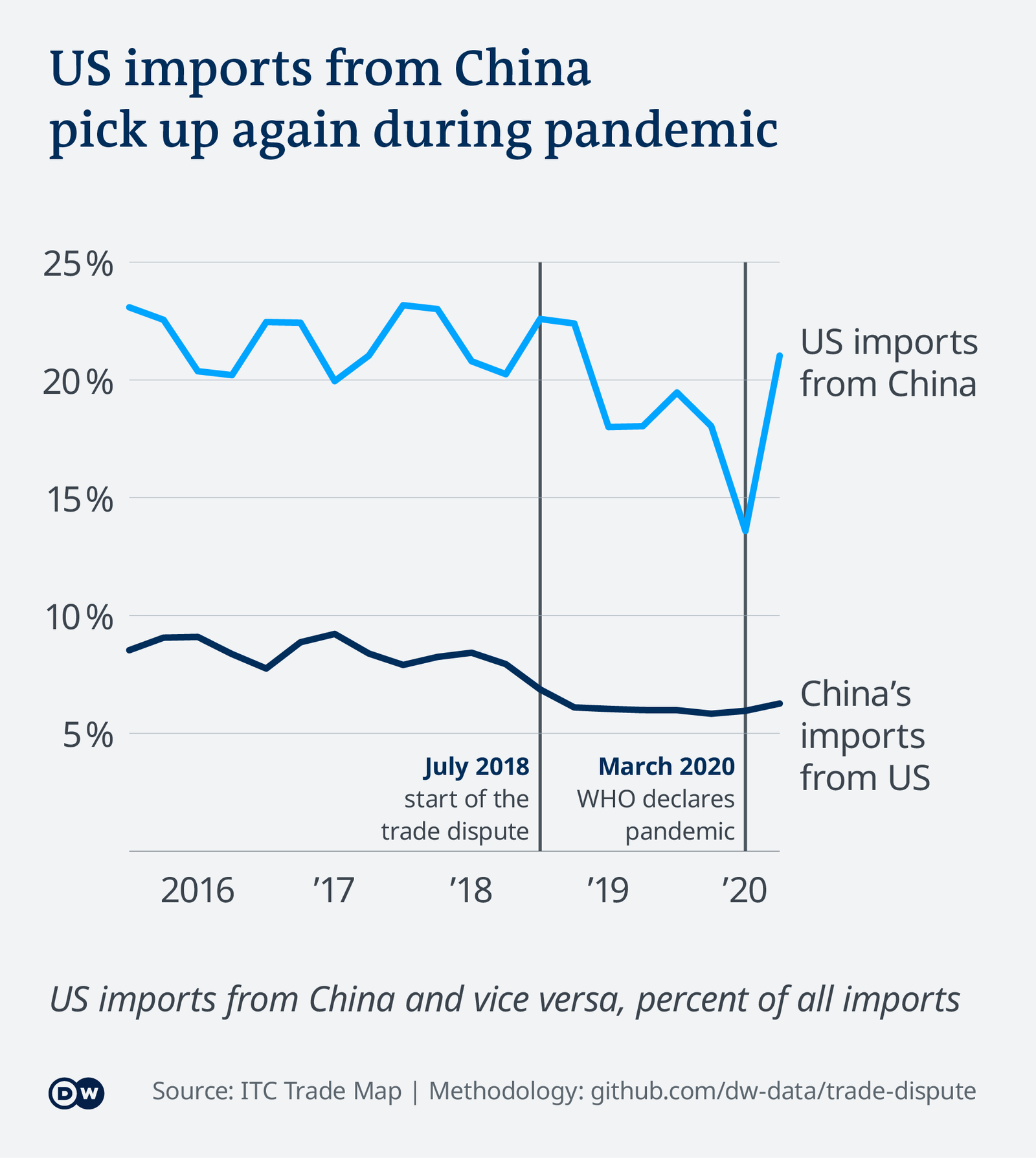

The tariffs have had a profound impact. Before the dispute began, 23% of all US imports came from China – more than $526 billion in 2017 alone, and roughly as much as neighboring Canada and Mexico combined. At the end of 2019, that was down to 18% – a decrease of more than $26 billion.

“The two biggest losers from the conflict are the US and China themselves,” says Yasuyuki Sawada, Chief Economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB). A 2020 ADB analysis finds that GDP and employment in both countries will suffer due to the conflict.

Imports from China fell during the dispute

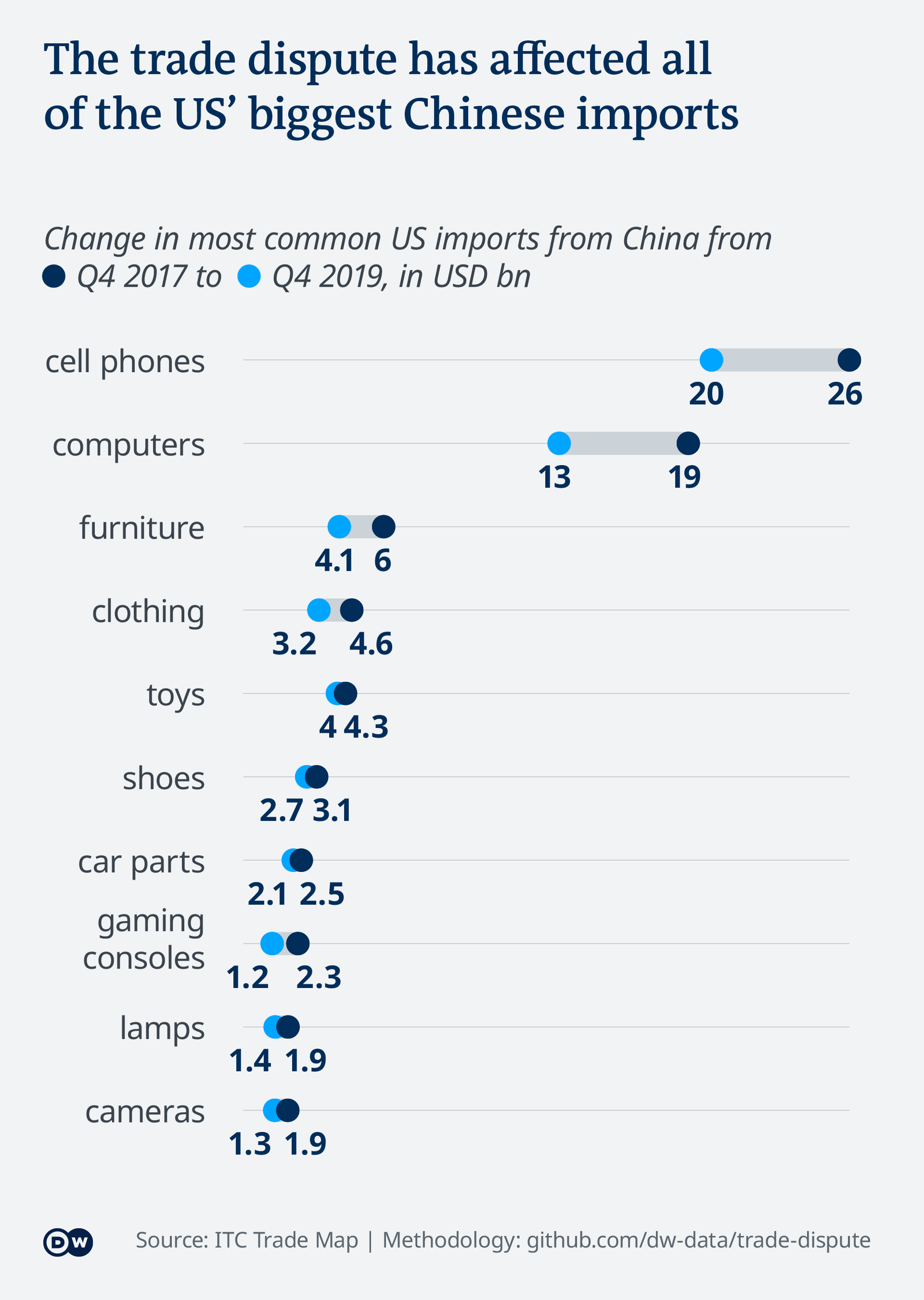

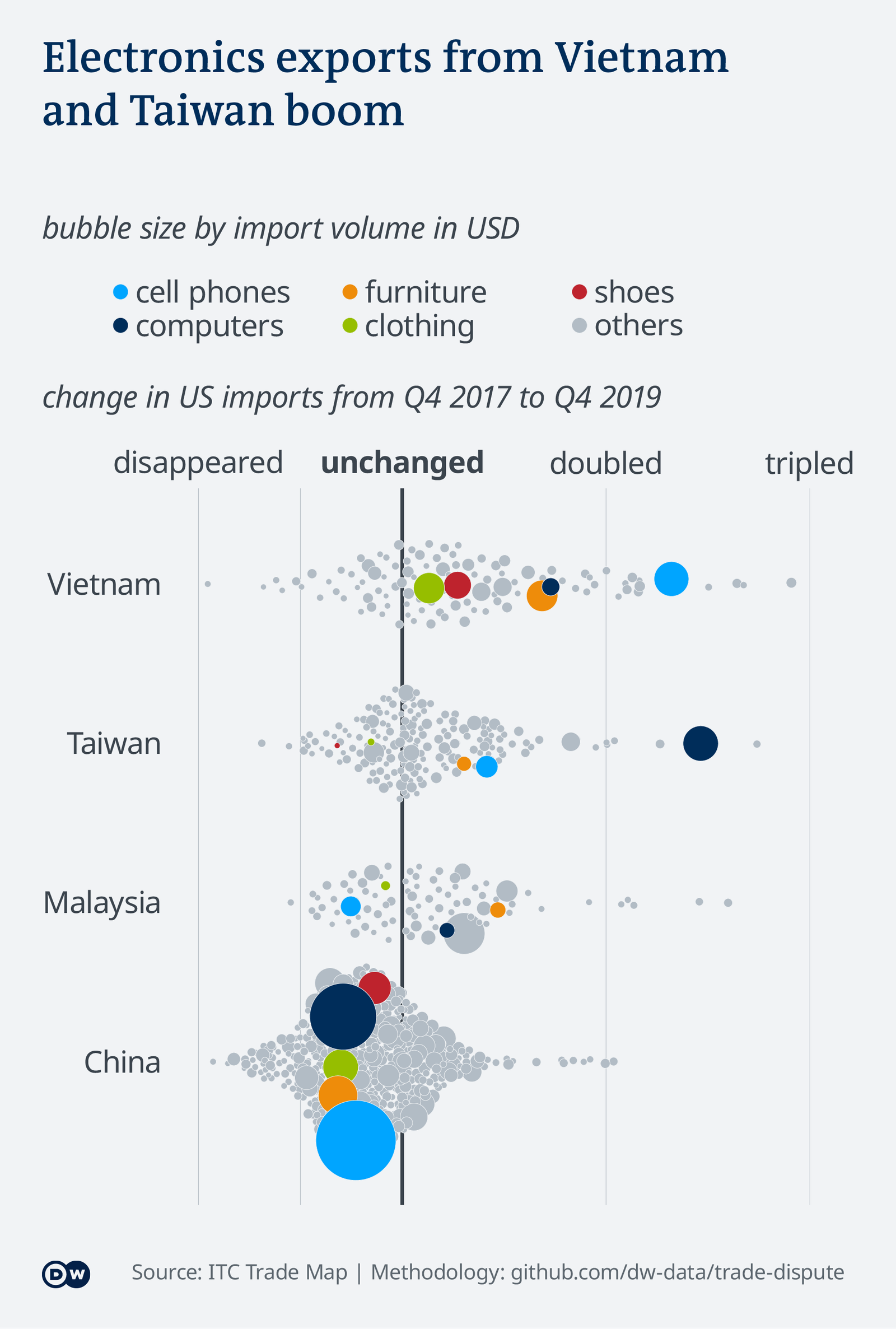

For US consumers, the dispute has largely meant that they have had to pay higher prices for Chinese products, while for China, it has mainly led to a loss in export value, a UN analysis found in November 2019. A look at the biggest Chinese exports to the US confirms that US firms were sourcing substantially fewer cell phones, computers, and furniture from the Asian economic powerhouse at the end of 2019 than at the end of 2017, before the trade war started.

2020: A trade truce and a pandemic

In January 2020, the US and China signed the Phase I deal, aimed at deescalating trade tensions. It called on China to buy billions more in US products in order to shrink the trade surplus that it enjoyed with the US. The condition was deemed unrealistic even before the deal went into effect. The pandemic has only made it more daunting.

“The requirements for additional imports of US products appear very, very challenging, given the growth of the Chinese economy will be much slower than forecast in January,” says Yasuyuki Sawada. In addition, the deal kept existing tariffs in place, effectively stalling the conflict instead of resolving it.

The pandemic that followed effectively disrupted global supply chains. But China’s economy has been able to bounce back since the second quarter of 2020. As one of the first major economies to come out of lockdown, it has been able to provide countries like the US with the products they need.

“Part of this was due to increasing exports of health supplies and equipment,” says Sawada. Imports of face masks from China to the US, for example, have increased more than 10-fold.

This has been helped by the many tariff exceptions granted by the US in the past months concerning products like not only surgical gloves and face masks, but also many electronic items, car parts and others. All this has boosted trade between the US and China almost back to pre-dispute levels.

But the effects of the trade war are still playing out. While prices for Chinese imports rose during the dispute, US demand in cell phones, computers, lamps or printers didn’t cease. As a result, US consumers and manufacturers are shifting to other countries to get the products they need.

Southeast Asia, Mexico benefited from trade dispute

For some, the gains from this trade redirection might even outweigh the negative effects of the dispute. “For non-China emerging economies, the positive impact dominates,” says Sawada. “The gain seems to be the largest for countries who can produce similar products to those made in China.”

Among those who benefited most was US neighbor Mexico: Between 2017 and 2019, the country exported an estimated $4.7 billion more to the US as a result of the trade dispute.

The added billions are especially significant for countries with lower GDPs, like Vietnam, Malaysia or Taiwan. Among them, Vietnam is the clear winner: The additional $6.4 billion gained during the two years of the conflict is equal to almost twice the country’s entire yearly health care spending.

This is the result of a DW analysis, which looked at goods imported by the US between 2017 and 2019 to find out which countries, and which industries, in particular, have benefited the most. One clue for the importance of an exporter is the market share that its products command among all products imported by its trade partner.

For example, China used to provide 62% of computers imported by the US. At the end of 2019, that was down to 44%, a loss of more than $5 billion.

But China’s loss was Taiwan’s and Mexico’s gain: They each gained around six percentage points in market shares. By the end of 2019, they provided 10 and 25% of all computers imported by the US, respectively.

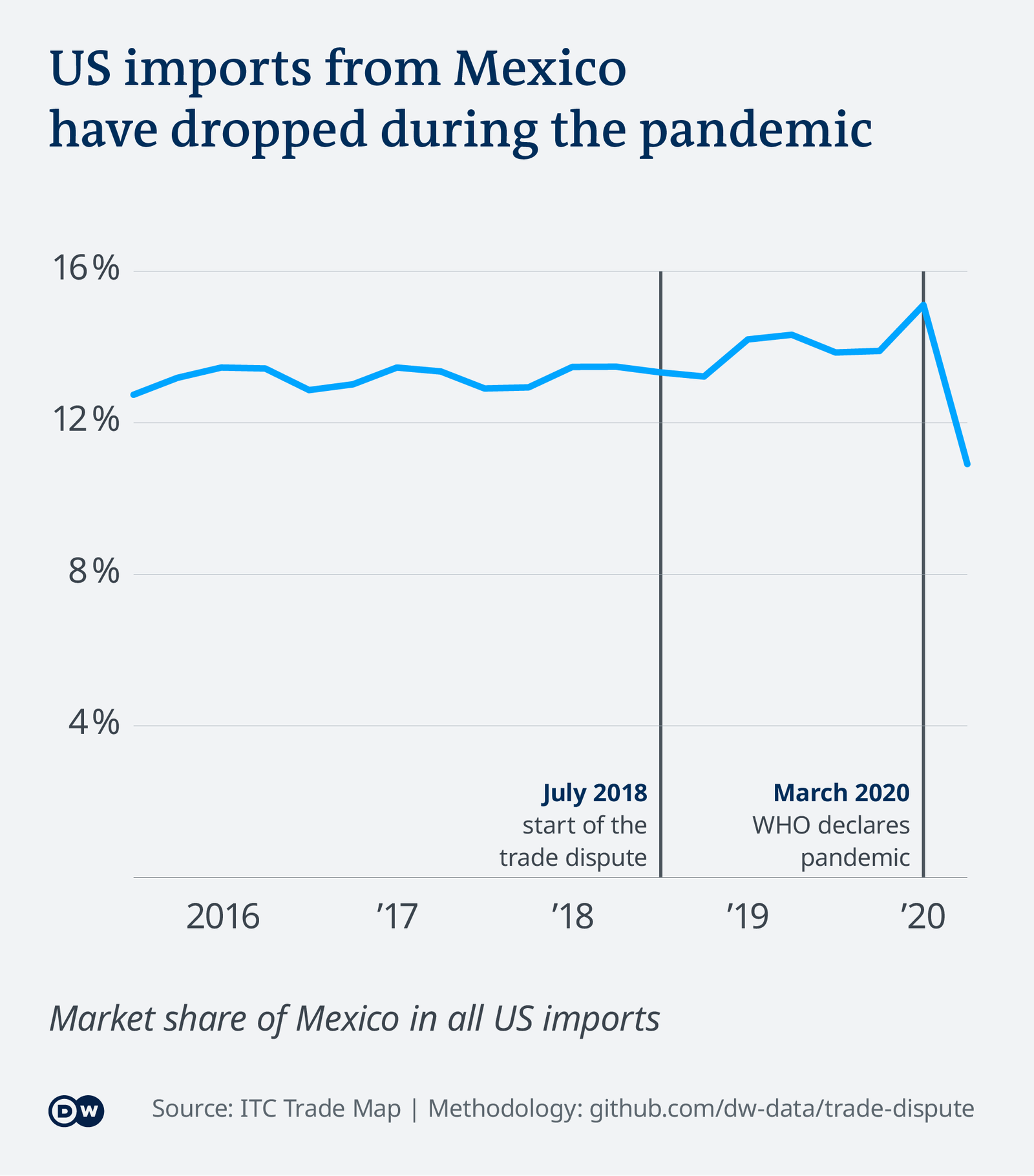

For Mexico, though, the pandemic disrupted the gains made in the past two years. Imports from Mexico to the US have nosedived; Even fewer products come from Mexico to the US now than before the trade dispute began.

But so far, Vietnam and other Southeast Asian economies have been able to hold onto their gains.

Some, like Vietnam and Taiwan, have even increased their exports to the US further.

That is partly because countries like Vietnam had long started positioning themselves as alternatives to China for foreign manufacturers. “Vietnam has progressively ramped up manufacturing, attracting foreign investors and increasing exports to the US,” says Khiem Vu, Vietnam manager at Global Resources, which connects companies to suppliers in Asia.

The trade dispute has accelerated the decision of multinational corporations to relocate from China, he says. “Many have forced their current Chinese manufacturers to shift production to Vietnam. For example, Chinese manufacturers that produce Crocs (foam shoes) have built multi-thousand worker plants in Phu Tho serving only the US market.”

Electronics from Vietnam in demand

Crocs isn’t the only shoe company making the move; Vietnam exported 30% more shoes to the US at the end of 2019 than it did two years back, while exports from China declined by 15%. “Labor-intensive products with high tariffs in China like bags, suitcases, glasses, apparel, furniture, tech and electronics could make Vietnamese suppliers more competitive than ever,” says Khiem Vu.

Even more than shoes or suitcases, it’s electronic items like the ones manufactured at Spartronics, as well as cell phones and computers, that have seen the biggest shift.

Vietnam more than doubled its cell phone exports to the US between end of 2017 and 2019.

For Spartronics, the pandemic has only accelerated its growth. “We are lucky to be in the right place at the right time,” says Dung Tran. Part of his business comes from manufacturing medical products like ventilators and, COVID-19 test kits. “That’s growing unbelievably. It’s compensating, with a surplus, the challenges we’re facing in our other segments.”

All of this has brought about visible changes in Vietnam, Dung Tran says: “I used to live in Silicon Valley, California. I can relate what we’re experiencing in Vietnam to the dotcom boom back then. If you’ve been in Vietnam before and you return back now, you’ll see more buildings, more skyscrapers.”

The question, he says, is how fast the country can scale up its infrastructure to deal with the growth. “All of a sudden, you have congestions at airports and ports due to the sheer volume of products coming through. The government is very committed to making an improvement, but it will take time.” And at the moment, it’s difficult to say what the next few years will bring.

Back to open trade for all

He is confident that the changes he’s seen in his business and across Vietnam are here to stay. “I think Southeast Asia and Vietnam will continue to grow regardless of these trade issues.” Still, he would prefer an end to the trade dispute: “We cannot live without China,” he says. “We need to depend on each other in a fair way. That’s very important.”

As this analysis shows, a trade dispute between two major countries today almost always affects others as well. “iPads and iPhones and gadgets are now produced using very complicated, tightly connected supply chain networks,” says Yasuyuki Sawada. “Chinese products facing lower production will affect suppliers of intermediate products. That will generate big negative spillover effects in Asian countries and economies.”

He too hopes for an end to the US-China trade tensions. “The Asian Pacific region has benefited so much from open trade in the last decades. I think it is very important, if at all possible, get back to before the US-China trade tensions era.”