The Trump administration has talked about bringing supply chains home from China, and even publicly floated the need for a group of friendly nations in Asia that could help produce essential goods. President Donald Trump last month even said the U.S. would “save $500 billion” if it cut off ties with China.

But interviews with nearly a dozen government officials and analysts in the Asia-Pacific region show that any broader effort to restructure supply chains is little more than wishful thinking so far. While governments are pushing to win investments, such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.’s planned state-of-the-art semiconductor factory in the U.S., it won’t be simple to dismantle an entrenched system when many companies are struggling to survive.

More likely is that the virus will accelerate a change that was already driven by market forces as rising wages and costs in China over the past decade caused an exodus of lower-value manufacturing, much of it to Southeast Asia. That’s despite the desire from some in the Trump administration to start decoupling the world’s biggest economies as the U.S. and China spar over everything from the virus to 5G networks to Hong Kong.

Not Decoupling Yet

“The rhetoric meets the reality, which is that many firms have supply chains set up the way they do for very sensible reasons,” said Deborah Elms of the Asian Trade Centre, which has seen an increase of companies looking for advice on reorganizing to increase competitiveness. “Coming out of Covid, it’s going to be even harder to move supply chains because your cash flow is low, your staff are working from home or coming slowly back into the office, and the business climate has shifted.”

While the world trade network mostly held up well amid rolling lockdowns as Covid-19 spread, the economic cost fueled calls among politicians for greater self-sufficiency and alternatives to China. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, whose department announced an Economic Security Strategy last year, in April named Australia, New Zealand, Japan, India, and South Korea as countries that the U.S. has been talking to on supply chains.

A key plank of the State Department’s new Economic Security Strategy is expanding and diversifying supply chains that protect “people in the free world,” according to Keith Krach, a State Department official who leads efforts to develop international policies related to economic growth.

Krach said in April a so-called “Economic Prosperity Network” of like-minded allies would be built for critical products.

‘China Plus One’

Industries would include pharmaceuticals, medical devices, semiconductors, automotive, aerospace, textiles and chemicals, among others.

But the idea right now appears to lack any firm foundation. The State Department doesn’t have jurisdiction over trade, and officials in other Asian countries said no formal talks were taking place. A person close to the administration said Krach is prone to pushing grand ideas publicly that haven’t yet become policy.

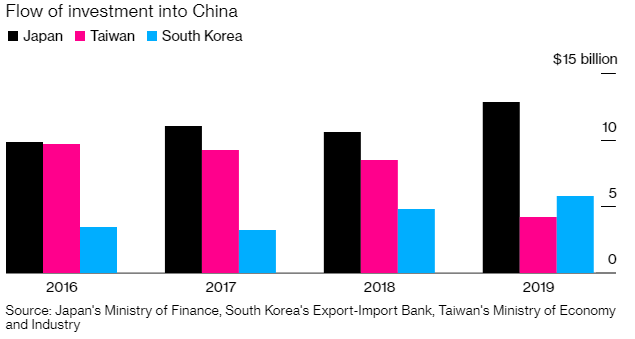

Still, other governments are moving on their own to shift production away from China — especially since the Covid disruptions. This includes Taiwan and Japan, which were among the biggest investors in China’s manufacturing capacity in the early days.

“Many companies have already begun adopting a ‘China plus one’ manufacturing hub strategy since the U.S.-China trade war began in 2018, with Vietnam having been a clear beneficiary,” said Anwita Basu, head of Asia country risk research at Fitch Solutions. While the pandemic will give that another push, “shifts away from China will be slow as that country still boasts an annual manufacturing output that is so large that even a group of countries would struggle to absorb a fraction of it.”